Down by Myrtle Creek

As seen in Bush Journal Vol.07

A two-way tarred road rolls towards Collinsvale in the Kunyani/Mount Wellington ranges of southern Tasmania. It becomes narrower as it passes through the tiny town and ascends into the range. Now a single lane of dirt, it’s a weave of twists and corners and—in the middle of the day, dapple-lit due to the dense eucalyptus species that envelope the mountains.

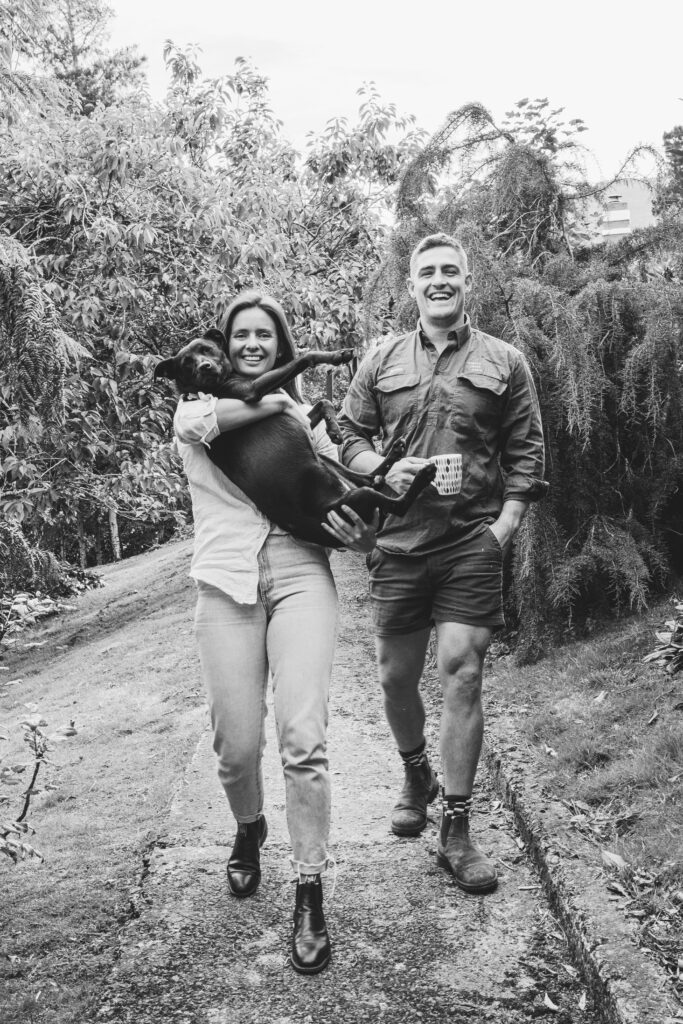

When the road widens ever so slightly, it reveals a wonky weatherboard one-car garage. Firewood is stacked neatly and to the left is a sturdy pine picket fence. Lilac hydrangeas border the gate, which two small black beady eyes peek through. They belong to Puddin’, a staghound cross who’s keen to know who’s arrived. Liz Dunlop appears from the weatherboard home, followed by her husband James MacAlpine. You can hear the trickling sound of Myrtle Creek echo from within the valley below.

“The draw to Tassie for Liz and I was the environment,” James says. “We’d both lived and worked in Sydney and Wollongong and were looking for something that enabled us a bit more space. We grew up in rural areas on farms and were keen to be based near a capital city but have the freedom to live in a more quiet and secluded area.”

Liz and James are what Tasmanians refer to as mainlanders. Born and raised in New South Wales, the recently-wedded couple decided on a move interstate during the Covid lockdowns. Liz works in marine policy for the federal government in Hobart, and James is a civil engineer at an infrastructure planning company.

After their initial move, they inspected the three-acre hobby farm 20 km north west of the city. In awe of Myrtle Forest which canvased their view from all angles, they fell in love with the heritage red-trimmed 1914 weatherboard home that sat on the side of Collins Cap and fringed the border of the national park. With the homestead, came riparian water rights to the use of Myrtle Creek and three run down, heritage-listed picker huts. Myrtle Creek Farm was established.

Liz and James dream of creating a natural immersive space for visitors, to spread awareness of how to live sustainably and work with the land rather than forcing it to be something it isn’t.

James’ engineering attributes shine through as he pulls out a very detailed laminated project plan showcasing their aspirations. “There’ll be three stages, which will happen over two to three years,” he says. “The first will be the installation of a spa and sauna located near Myrtle Creek—purely for relaxation purposes. Visitors will be amongst Myrtle Forest, listening to the sounds of the creek.

“The second stage will be renovations to our own home. Then the last stage will be renovating the pickers huts to provide self-contained accommodation for visitors.”

“One of the huts will pose as an interpretation hut,” Liz adds. “We’ll have the story of Collinsvale and Myrtle Creek Farm inside it and the process of developing our business.”

Collinsvale was formerly known as Bismark, but changed its name during World War II amid anti-German sentiment. The mountain ranges were popular for potato and hops cultivation—as well as logging that nearly wiped out the endemic myrtle beech.

“A lot of [them] were lost in the 1900s, but luckily the forest still holds unique pockets,” Liz says. “We’re trying to regenerate the tree by planting them around our home and down near the huts.”

Introduced species like foxglove, holly trees and radiata pines have infiltrated the pristine environment of these ranges, and threaten endemic flora.

“Because we’re on the border of Kunyani/ Mount Wellington National Park, we’re conscious that whatever we do plant, could spread into the National Park,” James says. “This is why we’re committed to regenerating the area with endemic species such as Australian blackwoods, myrtle beeches and Tasmanian pepperberry trees.”

The pair are are equally conscious of their access to the unspoiled Myrtle Creek, where the water glistens and the sun peeks through the leafy forest hollows above. They hope to install hydro electricity generators that will power their home and the pickers huts.

“Our home and our property are only small,” Liz says, “but we’re using all the space and incorporating as much of the natural environmental as we can. Our end goal is to be fully off-grid.”

The couple’s commitment to their home and the land creates hope the untamed mountain ranges and regions of Tasmania will remain just that —and those who choose to live there will do so with little impact.

“Whatever we add, we want it to be sympathetic to what’s already here,” Liz says. “We don’t want to over-commercialise our home. We just want people to see how you can live with the land.”

Sign up below to receive random newsletter mailouts when I can find the time, when I have new prints for sale, or in case Instagram shuts down and this is my only way to communicate with you in the future.

Info

It can be a little overwhelming taking the deep dive into marketing and communications. Let's talk over the phone or over a cup of coffee and see how we can work together to get your marketing strategy up and running.

© The Social Herd | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Shipping & Returns